Reversing Aging: The Cure for Alzheimer?

It’s just a matter of time that we will soon be able to reverse human aging. Does this mean that we will cure age-related diseases?

Yes, most likely.

One of the approaches that is gaining popularity is relengthening the telomeres of our cells. Telomere attrition is considered one of the primary hallmarks of aging (López-Otín, Blasco, Partridge, Serrano, & Kroemer, 2013), influencing also other secondary hallmarks (cellular senescence, epigenetic alterations…).

This approach becomes “simple”: if we’re able to reset telomeres’ length we’ll be able to reset gene expression, while increasing molecular turnover, cell maintenance and DNA repair (Fossel, 2002; Robin et al., 2014).

No need to kill anyone to become young again.

But ok now, how do we relengthen our telomeres?

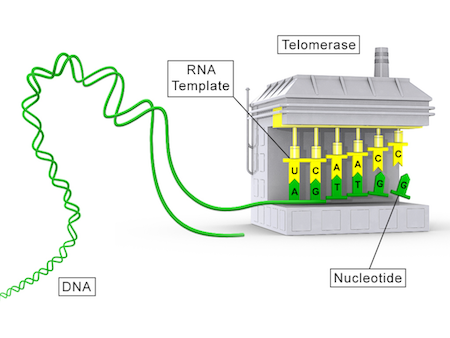

Naturally, telomerase is the enzyme that relengthes telomeres in humans. Telomerase acts a reverse transcriptase (Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase or TERT), adding to the DNA the complementary DNA (cDNA - sequence TTAGGG) using its RNA template (Telomerase RNA Component or TERC).

Unfortunately, telomerase is not active in our somatic cells. What then? This is where gene therapy comes to the rescue.

Gene therapy requires three things (Daya & Berns, 2008):

-

1) Identification of the defect at the molecular level (telomerase deficit)

-

2) A correcting gene (hTERT)

-

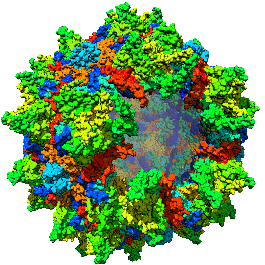

3) A way to introduce the gene into appropriate host cells (i.e., a vector - AAV9)

In our case we are interested in expressing telomerase in brain cells in order to prevent/cure Alzheimer’s disease. Adeno-Associated Virus are of special interest for this purpose, since they represent nature’s vectors for the delivery and expression of exogenous genes in host cells (Daya & Berns, 2008). Particularly using the serotype 9, since it has the capacity of crossing the Blood-Brain-Barrier (BBB). In that manner, we can infect brain cells, preferentially neurons and astrocytes (Foust et al., 2008; Manfredsson, Rising, & Mandel, 2009; Bernardes de Jesus et al., 2012).

How does AAV works?:

AAV9 confers the benefit of a high transduction (i.e. introducing DNA into cells) efficiency in a wide range of tissues, but if we’re interested in targeting Alzheimer we should worry about microglia.

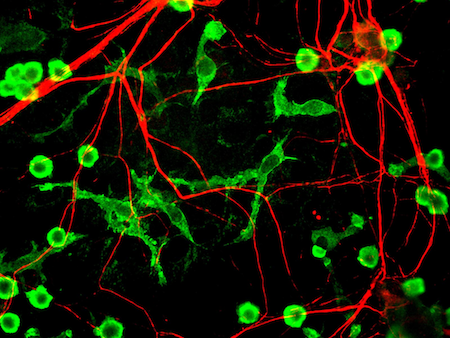

Microglia is of special interest for Alzheimer. Apart from being the immune sentinels of infection, they are also involved in the maintenance of brain homeostasis, in roles such as the control of neuronal proliferation and differentiation, as well as in the formation of synaptic connections (Ginhoux, Lim, Hoeffel, Low, & Huber, 2013). If we want to cure Alzheimer, we must restore microglial function, specially its degradative capacity that will avoid amyloid plaques to form in the first place (Solé-Domènech, Cruz, Capetillo-Zarate, & Maxfield, 2016; Yeh, Wang, Tom, Gonzalez, & Sheng, 2016).

Does AAV9 transduces microglia efficiently? It seems not. Here is where cell-specific promoters should be used. Both F4/80 and CD68 had already be proven to be successful transducing microglia (Cucchiarini, Ren, Perides, & Terwilliger, 2003; Rosario et al., 2016).

In summary, a gene therapy that makes possible to rescue senescent microglial cells to make them young again becomes promising for battling against neurological age-related diseases. Not only Alzheimer, but in a similar manner we’ll be able to fight against Parkinson, Huntington and others.

References

Bernardes de Jesus, B., Vera, E., Schneeberger, K., Tejera, A. M., Ayuso, E., Bosch, F., & Blasco, M. A. (2012). Telomerase gene therapy in adult and old mice delays aging and increases longevity without increasing cancer. EMBO Molecular Medicine, 4(8), 691–704. https://doi.org/10.1002/emmm.201200245

Cucchiarini, M., Ren, X. L., Perides, G., & Terwilliger, E. F. (2003). Selective gene expression in brain microglia mediated via adeno-associated virus type 2 and type 5 vectors. Gene Therapy, 10(8), 657–667. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.gt.3301925

Daya, S., & Berns, K. I. (2008). Gene Therapy Using Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 21(4), 583–593. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00008-08

Fossel, M. (2002). Cell Senescence in Human Aging and Disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 959(1), 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02078.x

Foust, K. D., Nurre, E., Montgomery, C. L., Hernandez, A., Chan, C. M., & Kaspar, B. K. (2008). Intravascular AAV9 preferentially targets neonatal neurons and adult astrocytes. Nature Biotechnology, 27(1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1515

Ginhoux, F., Lim, S., Hoeffel, G., Low, D., & Huber, T. (2013). Origin and differentiation of microglia. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2013.00045

López-Otín, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M., & Kroemer, G. (2013). The Hallmarks of Aging. Cell, 153(6), 1194–1217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039

Manfredsson, F. P., Rising, A. C., & Mandel, R. J. (2009). AAV9: a potential blood-brain barrier buster. Molecular Therapy, 17(3), 403–405. https://doi.org/10.1038/mt.2009.15

Robin, J. D., Ludlow, A. T., Batten, K., Magdinier, F., Stadler, G., Wagner, K. R., … Wright, W. E. (2014). Telomere position effect: regulation of gene expression with progressive telomere shortening over long distances. Genes & Development, 28(22), 2464–2476. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.251041.114

Rosario, A. M., Cruz, P. E., Ceballos-Diaz, C., Strickland, M. R., Siemienski, Z., Pardo, M., … Chakrabarty, P. (2016). Microglia-specific targeting by novel capsid-modified AAV6 vectors. Molecular Therapy - Methods & Clinical Development, 3, 16026. https://doi.org/10.1038/mtm.2016.26

Solé-Domènech, S., Cruz, D. L., Capetillo-Zarate, E., & Maxfield, F. R. (2016). The endocytic pathway in microglia during health, aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Research Reviews, 32, 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2016.07.002

Yeh, F. L., Wang, Y., Tom, I., Gonzalez, L. C., & Sheng, M. (2016). TREM2 Binds to Apolipoproteins, Including APOE and CLU/APOJ, and Thereby Facilitates Uptake of Amyloid-Beta by Microglia. Neuron, 91(2), 328–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2016.06.015